A microbe is any living organism which is too tiny to be seen with the naked eye. It is also called a microorganism, or a microscopic organism. The major groups of microorganisms are bacteria, archaea, fungi and viruses. Microbes are at the origin of all life forms. Microbes naturally live on and in our bodies. Often it is said that our own human body has 10 times as many microbial cells than human cells, and many of these live in the human gut The effect of microbes in our body is a relevant concern for health studies. Many of these microbes are ‘good guys’.

These microbes don’t live alone; like us they also thrive together as a community, known as a microbiome. In our guts, they help prevent colonization and invasion by pathogens (disease-causing microbes) by inducing protective responses from the host's immune system; competing with them for space and nutrients, and producing substances that can stop pathogens colonising and invading. to that,. In simple terms: "good" microbes fight against the ‘bad guys’ (pathogens) to keep us healthy. We know that some diseases, like colorectal cancer, are linked to having a disturbance or imbalance of the gut microbiome (dysbiosis).

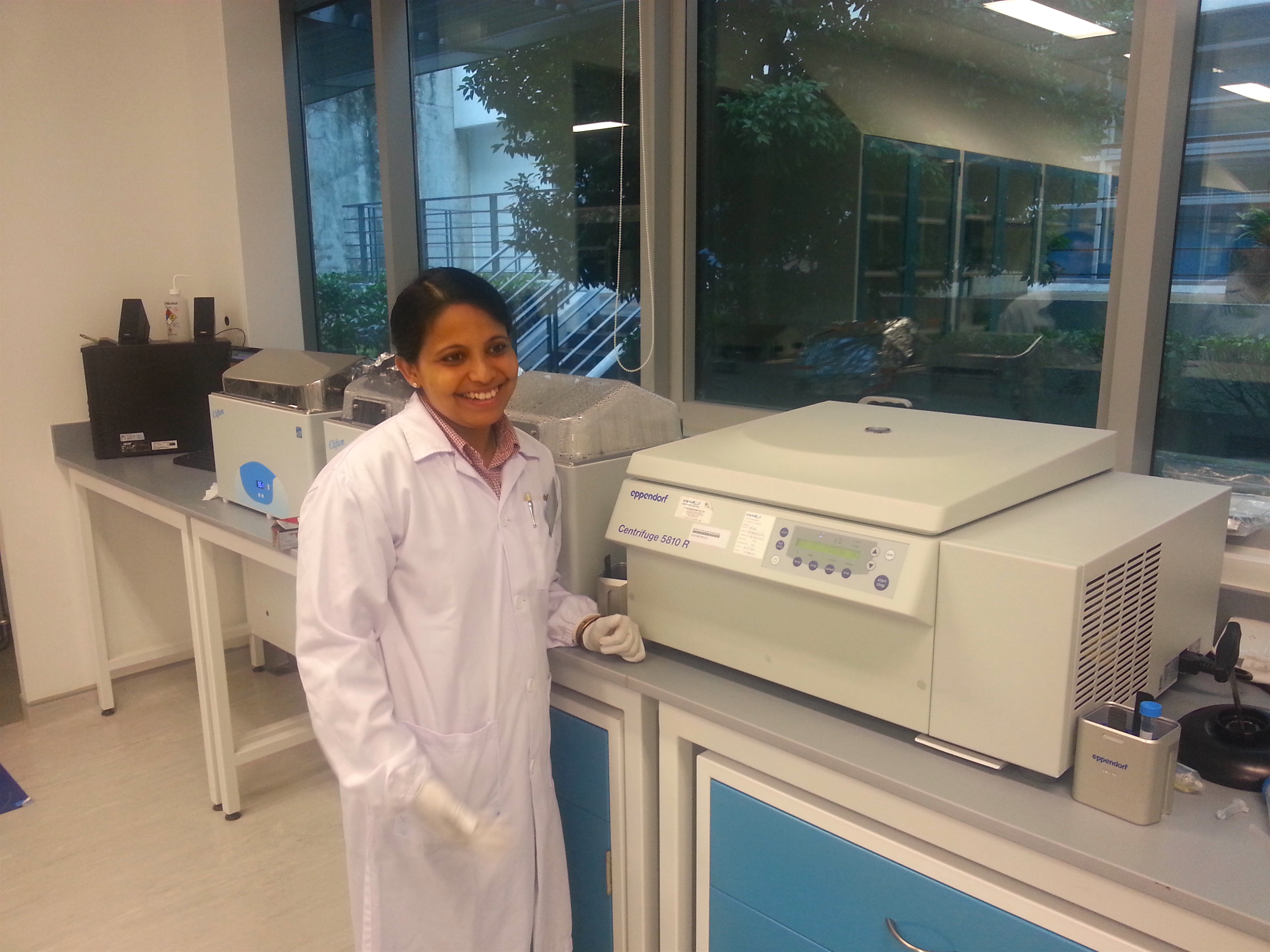

It is important to understand how the gut microbiome changes during colorectal cancer, and in response to any treatment, so that we can understand the disease better and design better treatments. One of the most informative ways we can look at the gut microbiome is metagenomics. This allows us to look at collect and look at the genetic material in poo from the gut microbiome and work out which microbes are there, and how abundant they are. By doing this at different timepoints or under different conditions (e.g. treatments), we can work out how the microbiome changes, and what those changes might mean.

In the COLO-COHORT study patients’ poo samples will be collected before their colonoscopy. These samples will be analysed to know the microbiome content and will also be correlated with multiple other factors like blood counts, food intake or phenotypic data (all kinds of clinical information regarding patients' disease symptoms, as well as relevant demographic data, such as age, ethnicity and sex). This microbiome data will be used to identify major trends in variation across the patients' cohort and also drivers of these variations based on the colonoscopy result.